Welcome to my website! I’m a writer who also makes furniture.

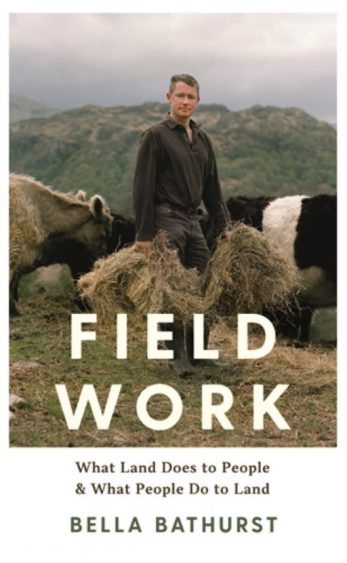

My books include The Lighthouse Stevensons, winner of the 1999 Somerset Maugham Award, The Wreckers, which became a BBC documentary and was shortlisted for the CWA Crime Writer’s Award, and Radio 4 Book of the Week Sound. My latest book Field Work was published by Profile in April 2021. On this site you’ll find all sorts of goodies including recent articles, some of the furniture I’ve been working on, excerpts from all my books, future projects, and details of how to get in touch with me.

Please fill in the contact form below. We will respond as soon as possible.