I had a couple of head injuries when I was in my twenties, and soon after the second one I started to go deaf. For a while I did what any well-adjusted adult would do; I pretended it would all go away. When that was no longer possible, I went along to the local audiology department who told me that my hearing in both ears was already down about 50%. They issued me with a pair of analogue hearing aids, and that was pretty much it – I just went home and got on with life.

There are lots of predictable things about losing your hearing, like not being able to hear the doorbell, but there are also lots of unpredictable ones. If you let it, it can change everything. It changes the car you drive or the way you use public transport. It changes the way you hold yourself physically. It even changes what you order in a restaurant. It probably won’t be steak or fish, because then you’ll be asked how you like your steak done or if you want a salad with that, so you’ll order something completely non-negotiable like pizza margharita. Whatever it is, it’ll be the thing requiring the least possible margin for error and the least possible interaction with another human being.

Hearing usually goes painlessly, but as it goes, it can take your social life with it. First of all you stop going to gigs or plays. Then to the cinema. Then to dinner parties or big work dos. Then you don’t go to the pub. Then it’s tricky going to the shops. Then you’re stuck down at the irrelevant end of the table during family meals. And finally it’s down to just you and the dog watching Strictly at full volume. All the things that connect you to other people – the phone, the office, evenings out – become harder and harder to negotiate.

To begin with, I hid it. When I met someone new it would have been easy just to say, ‘I can’t hear very well, I’ve got hearing aids but it would really help if you could speak clearly, keep facing me, and not cover your mouth.’ By doing so, I would have given them permission to ask and broken the ice. Instead I wore my hair over my ears so people couldn’t see the aids and struggled through, swiping for the one word in a sentence that I could hear or blanking people mid-sentence.

There are probably plenty of other people who would have coped fine in the same situation. But I’d found a condition – or a condition had found me – which was perfectly customised to my vulnerabilities. Just before I’d been diagnosed, I’d told a friend I thought I was losing my hearing. ‘You’re not deaf!’ he yelled. ‘You just don’t listen!’ That really hit home. I was a journalist and a writer, but perhaps I hadn’t listened properly to what people had said so now the capacity to do so had withered from me.

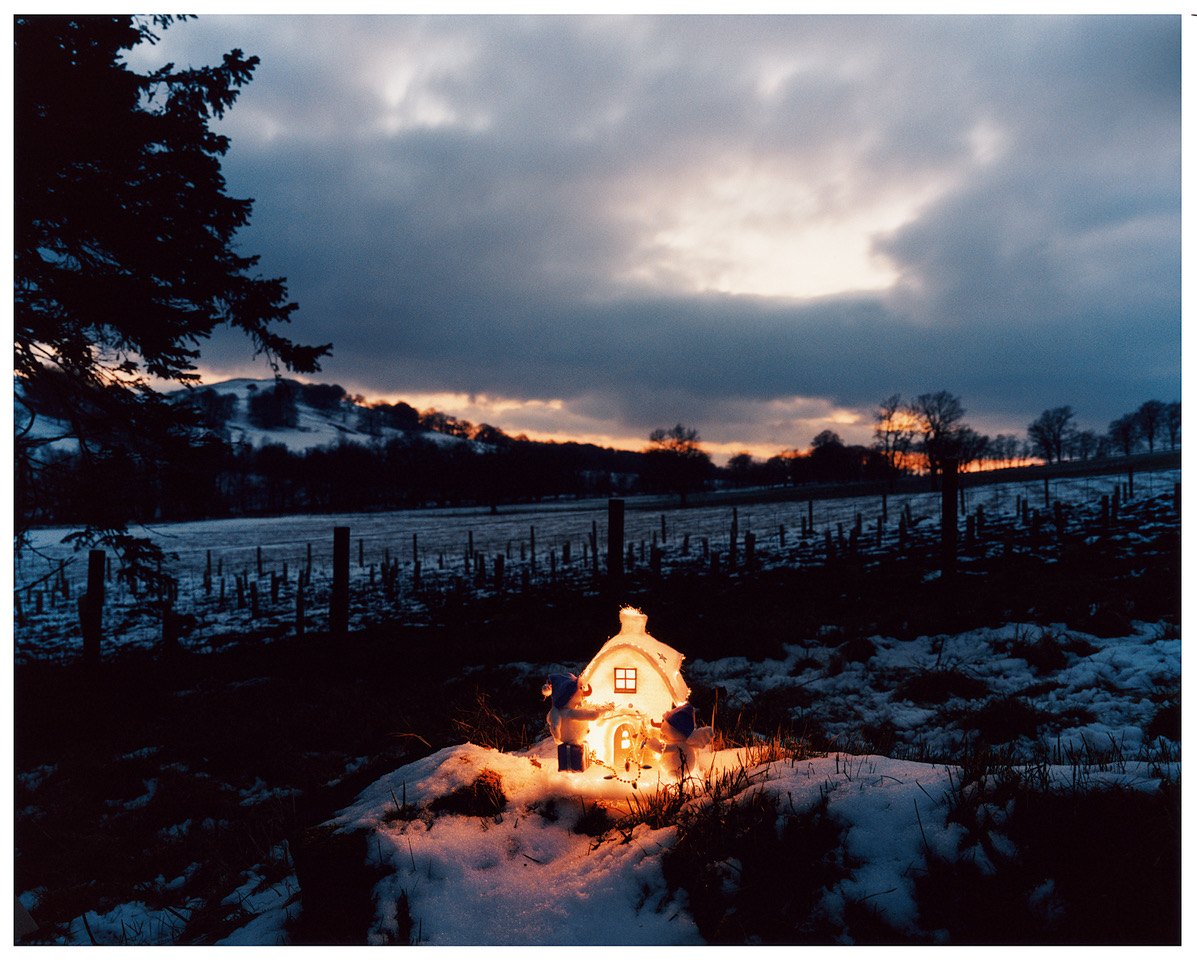

My hearing had been declining for about six years when two things happened. Firstly, I got a part-time job in a pro photographic lab, sleeving negs and contacting films. All day I’d stand by the lightbox, watching an endless technicolour procession of images (catalogue, editorial, advertising, gallery, catalogue …) slip through my fingers and down the line. As a visual education, it could hardly have been bettered. It didn’t just teach me how to look at photographs, it taught me how to see people – to read their body-language and really, properly see them. Both the prints and the printers taught me just how loudly people could talk without ever needing speech.

I also started looking for help. It turned out that those I needed were all around me anyway – friends, family, a few extraordinary individuals. To my surprise, they didn’t always mind if I misheard what they’d said five times or insisted that we met in cafes with good acoustics but disgusting food. All they’d wanted was to be there, all along.

And gradually, things started to right themselves. There are 11 million people in Britain with some form of hearing loss, and on average it takes them a whole decade to do something about it. Turns out – surprise surprise – everyone else is scared of the same stuff: loneliness, silence, isolation. But how can anyone possibly be lonely when there’s so many millions in exactly the same boat?

And then in 2009, I was rediagnosed. It turned out that the deafness wasn’t a result of the head injuries, it was a genetic condition called otosclerosis, a condition of the middle ear which also happens to be operable. Long story short, but following surgery, I got my hearing back.

For the first year afterwards, I just gloried in the pleasure of it. I eavesdropped compulsively; I sat on the top deck of buses and listened to long office bitching sessions in cafes, I took the seats on trains beside friends moaning about their love lives. Seven years later, I’m still delighted to be woken by car alarms or interrupted by security announcements. During those 12 years I learned how rich the silent world can be, but oh my God, I also learned to appreciate the sheer miracle of sound. Several millennia of evolutionary R&D has fitted all of us as standard with these pieces of jewellery, these stupendous things called ears. And all they ever ask of us is that we sit back, shut up and listen.